Secret Santa

by Meg Costello

Everyone loves the holiday lights on the Village Green, but such Christmas displays weren’t always welcome in Falmouth. The Congregationalists who settled our town treated December 25 as just another weekday. This tradition lasted well into the nineteenth century. When St. Barnabas church opened in 1890, Christmas finally arrived, if not on the Village Green, at least next to it.

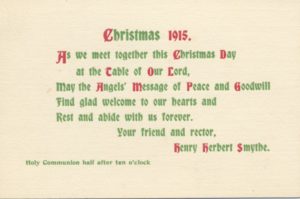

Pastor Henry Herbert Smythe described how his parish celebrated the holiday.

“For the Sunday School children, a large Christmas tree was placed in the library of St. Barnabas House. At the proper time the doors were pushed back and revealed the tree, beautifully decorated and lighted with innumerable Christmas candles, while all sang ‘The Wonderful Tree,’ which it indeed was, as celebration of Christmas in any form was unusual in Falmouth and a ‘Christmas tree’ a rare product of the season.”

Standing near the tree, the Beebe brothers handed out gifts. E. Pierson Beebe had purchased “skates, jackknives, and sewing cases, which gave universal satisfaction.” Frank Beebe gave a box of candy to each child and choir member, and to the organist.

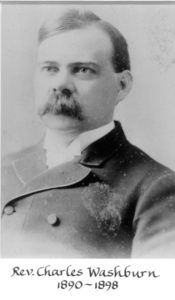

Watching all this fun from across the Green, some Congregationalists began to feel envious. Their minister, Rev. Charles Washburn, felt it necessary to preach a sermon to remind them “Why We Do Not Keep Christmas.” Little did he know that he was about to become a Christmas hero.

Watching all this fun from across the Green, some Congregationalists began to feel envious. Their minister, Rev. Charles Washburn, felt it necessary to preach a sermon to remind them “Why We Do Not Keep Christmas.” Little did he know that he was about to become a Christmas hero.

Rev. Washburn’s daughter Ruth was a student at Falmouth’s Village School, where she adored her teacher, Miss Ellen Bates. Ruth recalled,

“How well I recollect the Christmas when Miss Bates, assisted by Miss Frances Swift, set up a simply stupendous tree, decked with tinsel and real candles, and gifts for each child in the downstairs room. The gifts had been purchased from Miss Bates’s meagre salary at the additional cost of much time and sacrifice. The Selectmen, the Clergy, the School Committee members, all were there, invited to listen to the carols and share in the fun.

“As Miss Swift carefully lighted the candles, one after another, all held their breaths. One toppled over and immediately the whole tree was ablaze. One of the visiting men, with great presence of mind, hurled the flaming tree through a window into the snow bank below, amid the shouts and cries of dismay of the room full of children.

“Poor Miss Bates, to whom the burning tree meant the loss of all she had so long planned and saved for, put her head on her desk and sobbed audibly to the awe of us all.

“My minister father immediately put on his hat and hastened out on to Main Street, pencil and paper in hand. He went up and down the street, visiting every store, told the story of the mishap and the disheartened teacher, and returned with more money than had been invested originally. The response on the part of the merchants had been spontaneous and generous.

“The following day another tree (this time without candles), was erected in the school room and each child received a gift as well as an orange and a bag of candy. I still cherish the paper knife I received from that tree. It showed the marks of fire, but being metal withstood the smoke and flame, and so was salvaged from the first tree. In the shape of a fish, with the knife coming from its mouth like a spear, it was a most appropriate gift for a true lover of Cape Cod to receive!”

Rev. Washburn, the man who had preached against celebrating Christmas, turned out to be a Santa in disguise.